Understanding the GR Power Structure – Part VII: The relationship between local colleges, universities and systems of power in Grand Rapids

In Part I of this series I began an updated version of a Grand Rapids Power Analysis, which lays out the ground work for what the Grand Rapids Power Structure looks like and what it means for this community.

When I use the phrase, the Grand Rapids Power Structure and who has power, it is important to note that I mean power over. A local power analysis is designed to investigate who has power over – who oppresses, exploits and engages in policy that benefits them to the exclusion of everyone else – the majority of people living in Grand Rapids.

In Part II of this series on the Grand Rapids Power Structure, I looked at the DeVos family, which I argue is the most powerful family in this city, in terms of economics, politics, social and cultural dynamics.

In Part III of this series I looked at some of the other families and individuals that also wield tremendous power in this city, economically, politically and socially. In today’s post I will focus on the private sector organizations that also have tremendous power and influence on daily life in Grand Rapids.

In Part IV, I focus on private sector organizations, many of which have individuals who are part of the Grand Rapids Power structure sitting on their boards. These private sector organizations serve a vital role in dictating local policy, which primarily benefits their own interests.

Part V took a critical look at the role that the Grand Rapids City Commission and the Kent County Commission play in representing the interests of the private power sector, along with how they use fear and violence against residents who are actively challenging the local power structure.

In Part VI, I looked at how the major daily local news agencies normalize systems of oppression that protect and expand the Grand Rapids Power Structure. Today, I want to talk about the role of colleges and universities as it relates to the Grand Rapids Power Structure.

Colleges, Universities and Institutionalized Power

Dr. Henry A. Giroux, who has written numerous books on higher education, often critical, said the following in an interview:

Higher education must be understood as a democratic public sphere – a space in which education enables students to develop a keen sense of prophetic justice, claim their moral and political agency, utilize critical analytical skills, and cultivate an ethical sensibility through which they learn to respect the rights of others. Higher education has a responsibility not only to search for the truth regardless of where it may lead, but also to educate students to make authority and power politically and morally accountable while at the same time sustaining a democratic, formative public culture. Higher education may be one of the few public spheres left where knowledge, values, and learning offer a glimpse of the promise of education for nurturing public values, critical hope, and a substantive democracy.

While I agree with what Giroux is saying about what institutions of higher learning should be, they often fall way short of these ideals and have become increasingly centers of power, where free thought is limited and places where students and faculty that attempt to organize or take a principled stance are often marginalized or silenced. An example of how this has been playing out in recent months has been the student and faculty led movement in solidarity with Palestine, with demands on their schools to divest from Israel or entities that are complicit in Israel’s apartheid, occupation and genocide.

Amongst the universities and colleges in Grand Rapids, GVSU stands out as the best example of an educational institutions that acts as a buffer for those in power. This hasn’t always been the case, especially in the early years of Grand Valley State College, but once the DeVos Family became involved much of that changed.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, ever since Rich DeVos became a trustee at Grand Valley, the school went from being known as the Berkley of the Midwest to a university that collaborates with the Grand Rapids Power Structure.

Students at Grand Valley State College attempted to challenge the power of Rich DeVos in 1977, but the Amway co-founder offered the college an opportunity to not only become a university, but to shift its focus from a more progressive liberal arts college to a university that zealously embraces a neo-liberal capitalist view of the world.

Students at Grand Valley State College attempted to challenge the power of Rich DeVos in 1977, but the Amway co-founder offered the college an opportunity to not only become a university, but to shift its focus from a more progressive liberal arts college to a university that zealously embraces a neo-liberal capitalist view of the world.

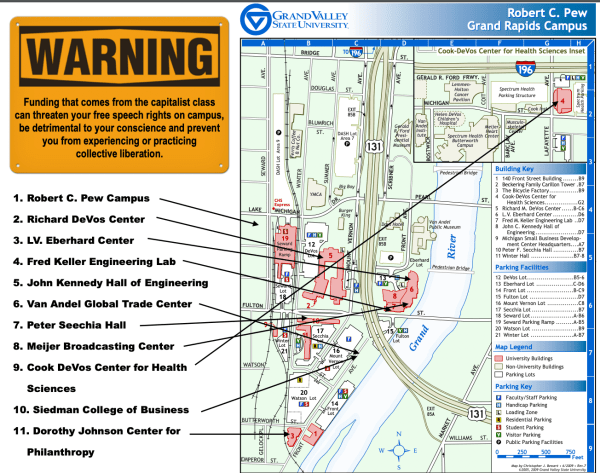

One indication of the embrace of neoliberal capitalism by GVSU can be seen in the so-called Wall of Fame, art the downtown campus, in the Eberhard Center. The Wall of Fame is made up of members of the Grand Rapids Power Structure, primarily business people, who have served on the board of trustees and donated large sums of money to expand GVSU’s economic influence.

Much of this influence is documented in our Popular Guide to Wealth and Influence at GVSU, which you can download at this link. One example we provide of how wealth has influenced GVSU politics has to do with what happened in the 1990s, when faculty members, who were part of the LGBT community, were told that they would be getting domestic partner benefits from the University. However, word of this promise became public and Rich DeVos and Peter Cook threatened to take away funding they had promised for the new Michigan St. building. Then GVSU President Lubbers, withdrew his commitment to the LGBT faculty and the new building got the funds it was promised.

Another way that GVSU feeds into the GR Power Structure is the increased focus on being a business school, which promotes Neoliberal economic policies. GVSU has been expanding this focus, with the growth of the Seidman School of Business and the Van Andel Trade Center. These programs are “complimented” by the Johnson Center for Philanthropy and the GVSU School of Social Work. These programs re-direct people’s energy into doing social work through non-profits, which focus on serving people who are marginalized in society, instead of being part of movements calling for systemic change. These career tracks generally don’t advocate for systemic change and they often do not even recognize that what is being taught in the business school actually causes the kind of social problems that the populations non-profits serve.

All of these dynamics are supported by those who run the university, such as those who sit on the Boards of Directors and those that make up the various foundations for local colleges and universities. You will notice in the links below how many people represent the business community, the financial sector and the development sector.

- Grand Valley State University Board of Trustees

- Grand Valley State University Foundation

- Calvin University Board of Trustees

- Aquinas College Board of Trustees

- Davenport University Board of Trustees

- Davenport University Foundation Board

- Cornerstone University Board of Trustees

- Cornerstone University Foundation Board

- Grand Rapids Community College Board of Trustees

- Grand Rapids Community College Foundation Board

Another aspect of GVSU’s function as part of the Grand Rapids Power Structure is that the current President Philomena Mantella, also is involved in several of the organizations that I mentioned in Part IV of this series, such as the Right Place Inc., the Econ Club of Grand Rapids, and Grand Action 2.0. In addition, Diana Lawson, the Dean of the Seidman College of Business, sit on the Board of Directors for the Grand Rapids Chamber of Commerce.

One last example of GVSU’s relationship to the GR Power Structure was the announcement in 2023 that GVSU would be partnering with organizations that are part of the local power structure to provide a “talent pipeline” for businesses.

Lastly, I want to say that I know plenty of faculty and staff at local colleges and universities, people which do good work and try to get students to think critically. I also know faculty that have had deep commitments to providing students with deep learning opportunities and experiences, only to be either marginalized or fired for doing so. This type of suppression makes it increasingly difficult for faculty and staff at local institutions of higher learning to take risks and to challenge those who run these schools, which more often than not function to normalize systems of power and oppression in Grand Rapids.

In Part VIII, I will talk about the relationship between religious organizations and the Grand Rapids Power Structure.

Trackbacks

Comments are closed.