Understanding the GR Power Structure – Part V: City and County Government

In Part I of this series I began an updated version of a Grand Rapids Power Analysis, which lays out the ground work for what the Grand Rapids Power Structure looks like and what it means for this community.

When I use the phrase, the Grand Rapids Power Structure and who has power, it is important to note that I mean power over. A local power analysis is designed to investigate who has power over – who oppresses, exploits and engages in policy that benefits them to the exclusion of everyone else – the majority of people living in Grand Rapids.

In Part II of this series on the Grand Rapids Power Structure, I looked at the DeVos family, which I argue is the most powerful family in this city, in terms of economics, politics, social and cultural dynamics.

In Part III of this series I looked at some of the other families and individuals that also wield tremendous power in this city, economically, politically and socially. In today’s post I will focus on the private sector organizations that also have tremendous power and influence on daily life in Grand Rapids.

In Part IV, I focus on private sector organizations, many of which have individuals who are part of the Grand Rapids Power structure sitting on their boards. These private sector organizations serve a vital role in dictating local policy, which primarily benefits their own interests.

In today’s post – Part V – I will focus on the local government bodies of Kent County and the City of Grand Rapids.

There are numerous functions that local government plays in supporting the Grand Rapids Power Structure. One primary function of local government (city and county), in supporting the area power structure, is to make sure that there is no significant threat to the existing power structure by members of civil society. Local governments practice defending the existing power structure by 1) making decisions, passing ordinances and creating budgets that will not threaten the existing systems of power; 2) limiting the level of direct democracy by civil society, and; 3) using force and fear to make sure that civil society does not challenge the existing power structure.

Promoting Business as Usual

While the Grand Rapids City Commission likes to present themselves as being progressive, they primarily function as conduit to maintain and defend the existing power structure. The Kent County Commission doesn’t present themselves as progressive, in the same way as Grand Rapids does, but they function pretty much the same way, in that they also are a conduit to maintain and defend the existing power structures.

Both the City and the County governments support the economic policy of “growth,” which ultimately means they defend the system of capitalism, which primarily rewards those who already have tremendous wealth and punishes those who do not. Growth, for the local governments, means providing massive taxpayer subsidies to the business community, especially to development projects, which primarily support those with tremendous wealth.

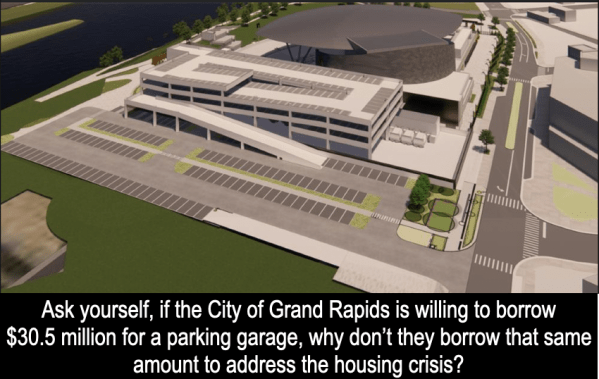

Since 2018, when I last posted a ten-part series on the GR Power Structure, the City of Grand Rapids has invested in hundreds of millions of dollars, especially into development projects in the larger downtown area. Projects such as the Amphitheater, the yet to be developed Soccer Stadium and the soon to be funded Aquarium. With just these three projects the City, Kent County and the State of Michigan have provided hundreds of millions of dollars in public money while large numbers of families are facing housing insecurity, food insecurity and poverty-level wages. This disparity in priorities, according to numerous City and County leaders, is primarily about attracting tourists and making Grand Rapids/Kent County a destination place for people to spend their money. This is exactly why the group behind the increased hotel tax, which will be used to fund these downtown development project, is called the Destination Kent Committee.

“Tourism is the backbone for our local economy. The amphitheater, soccer stadium, aquarium will help keep West Michigan on the map and draw people from all over to our great county.” Al Vanderberg – Kent County Administrator

While the City of Grand Rapids has been pushing tourism dollars in thee development projects that Grand Action 2.0 and the Grand Rapids Chamber of Commerce have been calling for, the City has adopted policies to benefit the business community, particularly in the downtown area.

One response from the City of Grand Rapids to the pandemic was to not only allow businesses to expand their outdoor seating, but the city created and provided public money for business districts. A second major response has been the criminalization of the unhoused, like what we saw during the pandemic in the GRPD clearing out Heartside Park, but also the two ordinances the city adopted in 2023.

Part of the reason that the Grand Rapids City Commission and the Kent County Commission support such policies is because many of them receive substantial funding from groups like the Grand Rapids Police Officer’s Association, the Grand Rapids Chamber of Commerce and members of the local power structure, like the DeVos family.

Limiting Direct Democracy

If people have ever attended City or County Commission meetings, they know that most of the decisions made at these meetings have already happened. Most agenda items are simply a formality, but the public is granted an opportunity to voice their concerns, which are heard by commissioners without any real feedback. Occasionally, there are public hearings, but ultimately the power to determine issues that merit a public hearing are still decided by commissioners at the city and county level. In other words, the public does not get to vote directly on major issues that impact the city/county.

Some will say that this is what representative democracy is and that it is the best we can hope for. Regardless of where one stands on the form of government that currently exists, the fact remains that the rest of us are limited in what we can do, if we play by the rules.

Take for example the issue of policing. A full one third of the City of Grand Rapids budget is devoted to policing. At the county level, a significant amount of the budget is set aside for the Sheriff’s Department, which includes the operation of the Kent County Jail. We know that the function of local law enforcement is primarily designed to police communities of color, to protect private property and to defend the interests of those with economic and political power. The amount of money, taxpayers money, that goes into local law enforcement is not something the public gets to vote on. The City and County Commissioners make those decisions and we are told to accept such outcomes. Regarding City and County budgets, it doesn’t matter if the commissioners are liberal or conservative, since they most of the commissioners endorse the City and County budgets, which means a great deal of money goes to policing, the jail, the court system and subsidizing privately run development projects.

Lastly, for the past three years Grand Rapids has been bragging about their Participatory Budgeting process, which is another cruel joke, since the amounts of money that people get to have a say in are small, plus the city limited the scope of how those few dollars can be spent.

Policing decent, Protecting Power

Policing dissent has certainly increased in recent years in Grand Rapids, although it usually comes in waves historically.

There are fewer things I can say about Kent County suppressing dissent, since most actions and protests happen in Grand Rapids, but there are some things worth talking about when it comes to Kent County.

Around the same time that the 2018 ten-part series on the GR Power Structure was being written, the immigrant justice group Movimiento Cosecha GR, along with an ally group, GR Rapid Response to ICE, began a campaign to end the contract between Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the Kent County Sheriff’s Department. The campaign lasted about 14 months, with no real support from county officials. In fact, ICE ended the contract, primarily because of all the negative attention the contract was getting in the local and national news media. You can read a People’s History of the End of the Contract Campaign in Kent County here.

In addition, during the pandemic, the Kent County Commission offered the City of Grand Rapids $500,000 to purchase the ShotSpotter technology, which community-based groups organized to defeat in the fall of 2020.

The list of ways that the City of Grand Rapids has policed and suppressed dissent is much longer. Here are a few examples:

- In February of 2019, immigrant justice activists disrupted the Grand Rapids City Commission meeting, because Mayor Bliss would not allow the same amount of time to community members that the Chief of Police was given to defend Captain VanderKooi.

- In March of 2019, a coalition of groups held a press conference with a list of demands around the GRPD and the lack of accountability regarding their actions against Black and Latinx communities.

- May 2019 march by Cosecha, was once again not attended by Mayor Bliss, plus the GRPD were now threatening people if they marched in the streets.

- GRIID obtained FOIA documents regarding the GRPD’s monitoring, spying, harassment and intimidation leading up to the 2019 May Day march.

- In May of 2020, Grand Rapids also had a George Floyd protest that erupted with thousands of people in the streets and the response from the GRPD was repressive. Mayor Bliss called for a State of Emergency, brought in the Michigan National Guard and instituted a curfew for downtown Grand Rapids. There was an effort to Defund the GRPD in late June/early July, which the Mayor derailed and numerous other repressive tactics used by the GRPD to target activists. You can check out our visual timeline of all this.

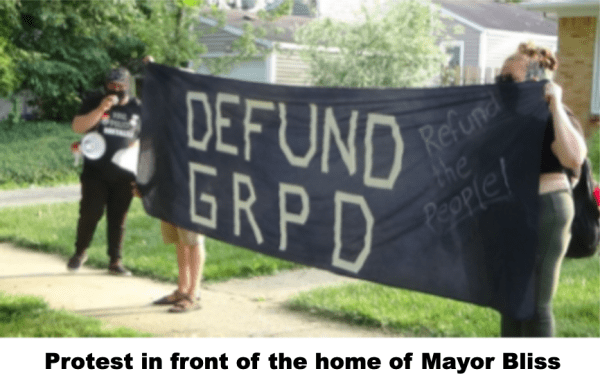

- In July of 2020, Defund the GRPD protested in front of the home of Mayor Bliss. (Pictured here below) She was not there, as she primarilY stays with her partner in Caledonia, which was verified by several of her neighbors who came out to talk with those protesting.

- In November of 2020, the community organized a campaign to defeat the GRPD from obtaining Shot Spotter technology. Mayor Bliss voted for it.

- In late December of 2020, Mayor Bliss gave the GRPD the green light to evict unhoused people who set up an encampment at Heartside Park.

- In April of 2021, the City of Grand Rapids sent out a Press Release saying that anyone protesting the outcome of the Derek Chauvin trial would be arrested.

- In May, the group Defund the GRPD was organizing to pressure the City of Grand Rapids to not only reduce funding for the GRPD, but to allow more public input on how public money would be used in the City Budget for 2022. In early May, the City held a one hour virtual town hall meeting on the 2022 Budget, which was an insult to those who have been organizing around how public money would be used. Defund the GRPD had posted their own demands on what they wanted to see happen with the funds, as well as the process for determining the 2022 City Budget. Defund the GRPD also organized people to call in during the City Commission meeting later in May, right before they voted on the 2022 Budget.

- Throughout much of 2021, the group Justice for Black Lives were targeted for demanding Police accountability in Grand Rapids.

- In November, at a protest following a not guilty verdict for Kyle Rittenhouse, several JFBL activists were arrested again, after the protest had finished. Once again, JFBL held a press conference to respond to the arrests and to counter the claims made by the GRPD.

- On April 4, 2022, the GRPD shot and killed Patrick Lyoya in the back of the head, execution style. Mayor Bliss has done nothing to further justice for the family of Patrick Lyoya, but has repeatedly allowed the GRPD to target activists who are demanding justice.

- In late December 2022, the Chamber of Commerce wanted to impose ordinances that would essentially criminalize the unhoused. During the last Grand Rapids City Commission meeting for 2022, Mayo Bliss and the other commissioners refused to denounce the Chamber’s proposal.

- Throughout 2023, Mayor Bliss fully supported the GRPD’s desire to purchase and use drones, plus she fully endorsed the Grand Rapids ordinances that has criminalized the unhoused in this city.

- After the brutal Israeli assault in Gaza, GR residents tried to get the City of Grand Rapids to pass a resolution demanding a ceasefire in Gaza and to call on members of Congress from Michigan to not use federal tax money that does to Israel but to use those funds to benefit our community. Mayor Bliss and the other commissioners said calling for a resolution is not what they do.

Despite the claims by the City of Grand Rapids to present itself as a family friendly city that embraces progressive values, they have a history of dismissing, ignoring and suppressing community-based movements demanding justice, especially those that are led by BIPOC groups.

In Part VI of this series I will focus on the role that the local commercial news media plays as it relates to the Grand Rapids Power Structure.

Trackbacks

Comments are closed.