William Glenn: Civil Rights Advocate in Grand Rapids, Communist Party member and Internationalist

William Glenn grew up in Grand Rapids. As an African American, Glenn was keenly aware of the racist and segregationist practices within Grand Rapids and most of its institutions.

William Glenn got involved in the Civil Rights struggle early on, as he was named in a lawsuit filed by the NAACP against the segregationist practices of the Keith Theater in Grand Rapids.

However, Glenn, like other more radical Grand Rapidians, was not always supportive of the efforts of the NAACP. In the 1940s, the NAACP leadership changed in Grand Rapids, and Glenn was one of several members that opposed what was called the Brough Community Association, a project that Glenn saw as a “Jim Crow project,” as is documented by Black historian Randal Jelks.

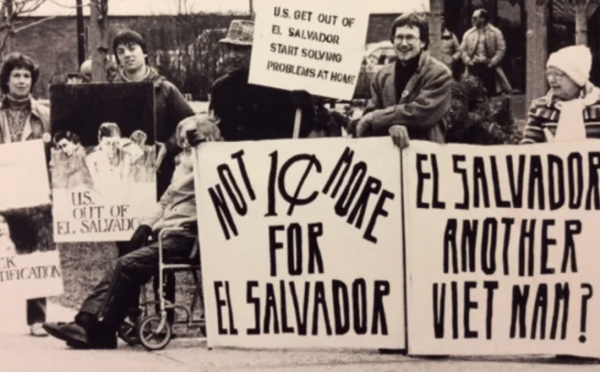

In this photo William Glenn is the person in the middle with a hat. Photo by Barb Lester

William Glenn was also a member of the Communist Party, something that made other NAACP members want to distance themselves from him. Because of his political affiliation, Glenn lost a job and in 1954 he was subpoenaed to testify in front of the US House Un-American Activities Committee.

However, efforts to silence and censure Glenn did not work. For most of his adult life, the activist continued to speak out on critical issues like racism and challenge US foreign policy. William Glenn is on the cover of my book, A People’s History of Grand Rapids, where he was part of a weekly Central American Solidarity protest that took place in downtown Grand Rapids in the 1980s.

William Glenn was also part of several labor unions, and he sat on the housing committee of the Community Relations Commission. Glenn wrote a three-page document addressed to Mayor Sonneveldt. The document was titled “Urban Renewal Housing.” Glen wrote the following about the housing crisis:

“It is a condition with which we can no longer play around. It is a condition that fifty years ago would have required dealing with a couple of square blocks – today several square miles must be dealt with. How large an area will it cover tomorrow? It is a condition that if not checked, can engulf the entire city.”

Glenn is correct in his assessment of the crisis and that it has been an issue for some time. We know that particularly in the city’s 3rd ward, specifically within the African American community, that the housing crisis was substantial. In a 1940 Urban League report, it states:

“In many instances the two-family houses are converted single family structures. Only one-fifth of the structures are in good conditions, one-third of them need either major repairs or are unfit for use. Nineteen families of the 205 (renters) do not have toilet facilities within their own unit; a greater number of families (84) do not have private baths. Over half of them live in cold water flats where they must furnish heat from small stoves, there being no central heating plant.”

That same 1940 Urban League report also states in the concluding remarks, “conditions in the Negro community are no better, if not worse, than at the time of the 1928 report.”

In 1947, the Urban League conducted another report on the State of the Black community in Grand Rapids. The 1947 report reflected very similar dynamics in terms of housing ownership and housing conditions, as the 1940 report. The reports cites the disparities between white and black residents when looking at housing, particularly at the cost of rent. A great deal of the housing disparities were due to structural racism, often in the practice of Red-Lining that plagued the black community for decades.

Another factor that contributed to the housing crisis in Grand Rapids, particularly for black people, was the construction of the highways through the city (196 & 131). In an interview I did with Fr. Dennis Morrow on this topic, he talked about 1,000 homes being destroyed and the devastation it had on families:

We don’t normally call it devastation, because something was built. It was pushed through by the government and certainly you could say that some people have benefitted from it. However, if the devastation from the riots of the 60’s had been nearly as great as the devastation wrought by the freeway construction they would have called the riots an all out war. The amount of dwellings that were destroyed during the riots were infinitesimal compared to those destroyed during the freeway construction.

The highway construction was part of the larger urban renewal efforts amongst city planners, often with the plan of wiping out or further marginalizing black neighborhoods.

Glenn goes on to say that it is the city’s responsibility to address the housing crisis by investing massive amounts of money and appointing someone who would coordinate this effort. Glenn concludes that this communal effort cannot be done in piecemeal fashion and that the longer we wait, the worse it will get. “The longer the task of saving the inner-city is delayed, the more difficult – if not impossible – it becomes to accomplish. It is a task which can never be accomplished in piecemeal fashion as some are attempting to do.”

At one point, Glenn refers to the “power structure of the city,” showing his critical understanding that the power structure was not limited to elected officials but included many institutions and a small group of wealthy families, all of which shifted dollars and influence away from neighborhoods in order to invest in the downtown area.

For more information on William Glenn, see the book by Randal Jelks, African Americans in the Furniture City: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Grand Rapids. Also see the complete three-page letter that Glenn wrote in 1970 about the housing crisis in Grand Rapids. https://grpeopleshistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/1970-document-on-the-grand-rapids-housing-crisis.pdf

Comments are closed.