Campesinos reclaim some communal lands in Mexico that Amway has been using for their Nutrilite product line

I read an interesting story on Crain’s Grand Rapids Business yesterday, which centered around a land dispute between the Amway Corporation and Mexican farmers.

The Crain’s article headline reads, Inside Amway’s failed $2.7B claim over seized Mexican farmland. Early on in the story it states:

The dispute follows a 2022 land seizure that has been in arbitration since 2023. Amway affiliate Access Business Group has racked up nearly $3.5 million in legal costs to protect the company’s interest in a plot of land known as Rancho El Petacal that the Ada-based direct selling giant purchased in the early 1990s for its Nutrilite supplement operations.

This article is instructive in so many ways. First, the Crain’s article is written almost entirely from the point of view of the Amway Corporation. At one point in the article readers do hear from someone other than Amway:

“This land has been stolen, first by the landlords of the hacienda, and then came the worst, when the government handed over the land to a transnational company instead of us peasants,” Raúl De la Cruz Reyes, chairman of the San Isidro ejido, told publication Pie de Pagina in 2022. “This company destroyed the fauna, everything. They take the product but the people remain poor because the wealth is taken abroad. What is left here are people who are worn out from work and a few elites who are filling their pockets with money.”

Second, without looking into the claims of those who have communal land rights, the Crain’s article shifts gears and talks to a Grand Valley State University Seidman College of Business professor, who was also cited at length early on in the article.

Third, when discussing the arbitration component, the Crain’s article states:

In its 2023 arbitration request, Amway argued its investments reflected the company’s commitment to its Mexico operations and benefited the local economy.

The investments included the construction of a nearly 4-mile highway to the farm, a bridge and a water treatment plant for the local community. Amway said it contributed financially to the construction of a local church, a soccer facility, and to maintenance of an elementary school facility. Amway also built a community center where Nutrilite has sponsored events such as English language courses, arts workshops and nutrition programs.

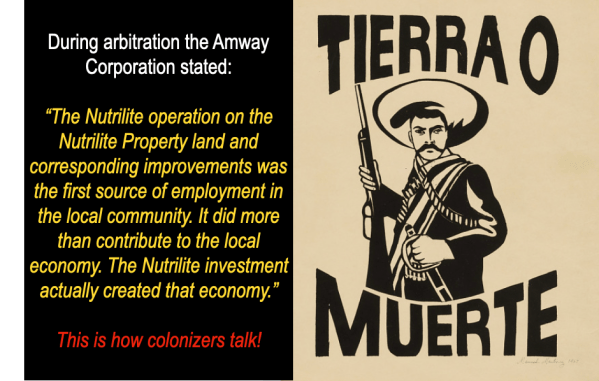

“The Nutrilite operation on the Nutrilite Property land and corresponding improvements was the first source of employment in the local community. It did more than contribute to the local economy. The Nutrilite investment actually created that economy,” the company said in the arbitration request.

What the Crain’s article suggests is that the people from the community had nothing before Amway arrived and made their lives better. Fortunately, there is another narrative. In an article headlined, San Isidro vs Amway, it states:

The communities brought their case against Amway to the United Nations and to the Permanent Peoples Tribunal. They denounced the company for violating their right to use their lands, not only to grow their foods but also to access water and move freely across their territory. They also denounced the company for environmental damage, contaminating water sources and causing health impacts such as cancer, kidney damage, and poor childhood growth. The community also decried how, without access to land, they were forced to work for the company, in poorly paid and precarious conditions.

This paints a fundamentally different narrative from the one that the Amway Corporation wants to portray. I found another article written in an online publication called Ojala, with the headline, The long road to getting land back in Mexico. This article also presents a very different narrative than the Crain’s article, which relies primarily on Amway’s narrative. Here is one excerpt from that article:

In 1994, U.S. company Amway/Nutrilite S.R.L. de C.V., bought the land from the former plantation owners, who were in deeply in debt, under the regulations of the North American Free Trade Agreement. According to attorney Robles, the company did so knowing that the land title was disputed. The company purchased the land nonetheless, while accepting liability for any conflict that might occur. It never complied with the agreement that its representatives signed. Amway has asked the courts to affirm its claim to the land, but this should be dismissed given this clause, according to the ejidatarios and their lawyer.

Ojalá attempted to contact Amway’s communications department via phone and email to inquire about the reasons for its lawsuit, despite having agreed during the purchase to assume the consequences of having acquired the land in default. We have not yet received a response.

It warms my heart to read of the possibility that communal lands might be restore to Indigenous people in Mexico. During the Mexican Revolution over 100 years ago, one of the principles of that revolution were captured in the phrase – Those who work the land ought to own it collectively!

It should surprise none of us who live in West Michigan, that the Amway Corporation is seeking to keep land that did not belong to them. The Amway Corporation should be seen clearly in this case as the outsiders and the colonizers of land they have no right to. As the Mexican Revolutionary Emiliano Zapata once said, “Tierra o Muerte!” “ Land or Death!”

Comments are closed.