Viva Flaherty – Radical Socialist who documented the furniture workers strike and resisted WWI in Grand Rapids

Last week I posted a story about Voltairine De Cleyre, a feminist and anarchist writer who lived in Grand Rapids in the 1880s. Today, I want to draw attention to Viva Flaherty.

Last week I posted a story about Voltairine De Cleyre, a feminist and anarchist writer who lived in Grand Rapids in the 1880s. Today, I want to draw attention to Viva Flaherty.

At the time of the 1911 Grand Rapids Furniture Workers Strike, Viva Flaherty was working as the office secretary at Fountain Street Church, which was a Baptist Church in the early part of the 20th Century.

Viva Flaherty documented the 1911 strike because she believed that the “people of Grand Rapids are awakened and enlightened and they can be trusted with the whole truth.” Flaherty went on to say, in her introduction to the History of the Grand Rapids Furniture Strike:

“A strike is a public matter, and if the people are to know how another is to be avoided they should know all the inside facts of this one, so that they may know whom to distrust and on whose shoulders rests blame for a nineteen weeks strike.”

Flaherty makes it clear in her version of the story that the strike was able to endure as long as it did because of the seven unions that were involved, with membership of over 4,000 workers in thirty-five shops in Grand Rapids. She also made it clear in the opening observations of her historical account that the Christian Reformed Church would not grant their members the right to be part of the union, since it was not “founded on divine right.”

On page 8 of the booklet written by Flaherty, she documents the kind of wages earned by those in the furniture industry, stating that of the eight thousand furniture workers employed in Grand Rapids, most made less than $2 a day. Flaherty also mentions that as early as 1909, after furniture workers found out that the price of what they produced had increased by 10%, they demanded that their wages increase. Some of the workers who had made such demands in 1909 were fired shortly thereafter as being agitators.

A commission was established to investigate the grievances of the workers, which included a final report. However, according to Flaherty, the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners had designated the commission as, “the hired servant of that powerful union, the Furniture Manufacturers Employers’ Association.”

Such suspicions were affirmed by the furniture industry’s claims that they needed to honor any of the demands from the striking workers around wages, hours, piece work, etc. Flaherty notes that the furniture barons, “repudiated any social responsibility to regulate wages to suit the cost of living.”

On page 17, Flaherty affirms the workers admiration of Bishop Schrembs when she writes:

Such commentary not only reflects that Schrembs was practicing the social gospel, but it also reflects the sophistication of Flaherty and her keen theological observations. What a powerful indictment she makes of the church that endorsed the furniture barons, by stating that they worship the Almighty God of the Pocketbook.

Flaherty then goes on to talk more about the specifics of the strike, beginning on page 18, where she discusses the “riot” on May 15. The “riot” Flaherty was speaking of is when workers and their wives confronted strikebreakers & scabs who were brought in to continue with production after the walkout of 7,000 furniture workers.

It is worth noting here that during the confrontation against the scab workers, many of the women in the crowd, who had been hiding rocks and bricks under their dresses began to throw them at the scab workers and cops who attempted to escort them into the factories. Such disgust at the attempt to break the strike by the furniture barons is captured in the statue dedicated to the 1911 furniture workers strike. At the feet of the woman depicted in the statue, you can see rocks underneath her dress.

The City of Grand Rapids, for its part, not only called for arbitration during the strike, but adopted this resolution on July 24, 1911:

Towards the end of the booklet, Flaherty provides more forceful observations about the furniture industry and reflects a high level of class consciousness that workers had developed in the early part of the 20th century. Flaherty states:

“Capital knows that when the people realize that capital is organized in this country today for the conscious and deliberate purpose of crushing labor in its efforts to become free, the people will make common cause with labor and send the divine right of capital to join the divine right of kings. Industrial freedom is a state which the world as yet has not experienced.”

Flaherty then follows up with a clear indictment against the captains of industry, particularly the National Association of Manufacturers and the Furniture Manufacturers Employers’ Association. These entities were producing their own propaganda that blamed workers for being “class conscious” and for “stirring up trouble.”

Resisting World War I

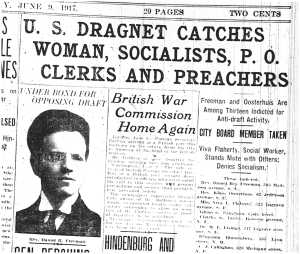

In May of 1917, several members of the Socialist Party, two clergymen and Feminist/Labor supporter Viva Flaherty were arrested in Grand Rapids for distributing anti-conscription pamphlets near downtown Grand Rapids.

In May of 1917, several members of the Socialist Party, two clergymen and Feminist/Labor supporter Viva Flaherty were arrested in Grand Rapids for distributing anti-conscription pamphlets near downtown Grand Rapids.

This seemingly mild act of informing people about their rights and about the imperialist nature of World War I was seen as a form of treason. There had been numerous laws passed since the beginning of the United States government, such as the Alien and Sedition Acts passed in 1798, which meant to silence and punish those considered to be, those “dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States.”

The Espionage Act was passed in 1917, as a means to silence and punish those who spoke out against the US entry into World War I. However, as radical historian Howard Zinn points out, these laws were not applied equally and were meant to target dissidents during WWI, particularly radical labor organizers, socialists and anarchists. Some of those arrested for opposing the US entry into WWI were arrested and jailed, while others were arrested and deported.

The level of contempt that the US government held against radicals involved in labor organizing and anti-WWI activities eventually led to the Palmer Raids (1919-1920) as a justification for “cleansing” the US of radical leftists, socialists and anarchists.

Those arrested in May of 1917 in Grand Rapids fell under the category of dissidents and radicals. There were several who identified as Socialists and then there was Viva Flaherty. Flaherty was the only woman arrested in May of 1917, but she was possibly the most well known of the group, particularly in Grand Rapids.

Flaherty, along with those she was arrested with, were passing out anti-conscription pamphlets on Division Avenue near downtown Grand Rapids and on Bridge Street. They had 15,000 copies printed from the Furniture City Printing Company of Grand Rapids.

The International Socialist Review, published in Chicago, makes mention of the action taken by the state against Viva Flaherty and her fellow dissidents. Published in the July 17 edition of the ISR, this is what they had to say about the anti-conscription action:

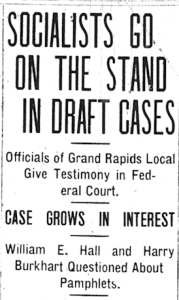

Almost all active members of the Socialist Party have been arrested and indicted by a Federal Grand Jury. Principal charge is that the accused, by the circulation of literature and “thru demonstrations, mass petitions and by other means,” conspired to “prevent, hinder and delay” the execution of the conscription law. There were six counts in the indictment.

Almost all active members of the Socialist Party have been arrested and indicted by a Federal Grand Jury. Principal charge is that the accused, by the circulation of literature and “thru demonstrations, mass petitions and by other means,” conspired to “prevent, hinder and delay” the execution of the conscription law. There were six counts in the indictment.

National Secretary Adolph Germer, of the Socialist Party, was also indicted by the same jury and charged with conspiracy. On learning the “news,” Comrade Germer went to Grand Rapids, submitted to arrest, plead “not guilty” and was liberated on bonds. If necessary, these cases will be carried to the highest courts.

Grand Rapids has a population around 130,000—mostly wage slaves. Scab labor runs its factories. It is a typical American Billy Sunday burg. Therefore all the fury of the pulpit and the press was directed against the socialists.

Among the indicted comrades are Ben A. Falkner, financial secretary of the Local. For years he has been employed in the city water works department. He has been fired and blacklisted by the political patriots. Comrade G. G. Fleser, corresponding secretary of the Local, who had worked eight years for the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad as a stenographer, was discharged by the patriotic rail-plutes. Viva L. Flaherty, social worker and writer; Charles G. Taylor, member of Board of Education; James W. Clement, manufacturer; Charles J. Callaghan, postal clerk (discharged); Dr. Martin E. Elzinga; G. H. Pangborn; Vernon Kilpatrick; Rev. Klaas Osterhuis, and our wellknown, active old-time Comrade, Ben Blumenberg.

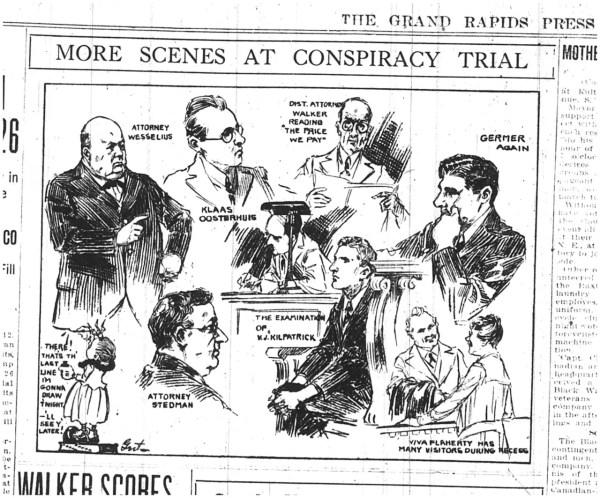

The Grand Rapids Press wrote about the arrests, the selection of the jury and the trial itself. Much of the their reporting reflected a bias in favor of prosecution of those arrested for distributing anti-conscription material. There were a few interesting cartoons that ran during the trial in October of 1917, one with the note below Viva Flaherty’s image which says, “Viva Flaherty has many visitors during recess.”

Ultimately, Viva Flaherty and her co-conspirators were not found guilty for the charges brought against them from May of 1917. The trial ended on October 18, 1917, and it well documented by the National Socialist Party in the publication entitled, “Not Guilty.”

Viva Flaherty may not be well know, especially for her opposition to the US entry to WWI and the military draft, but future generations should look to her for inspiration as someone who challenged political and economic power structures in Grand Rapids. Flaherty lived to be 84, eventually dying in 1968.

Trackbacks

Comments are closed.