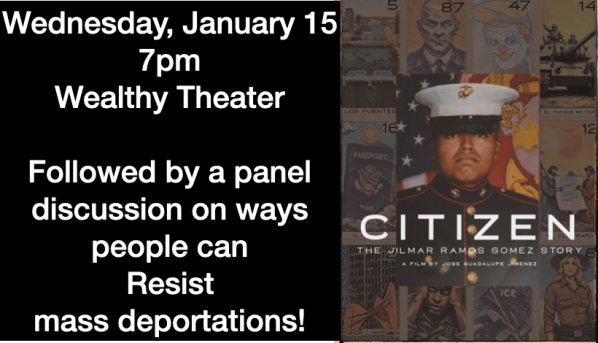

Interview with Jose Guadalupe Jimenez Jr on his new film to be screened at the Wealthy Theater on January 15

GRIID – You have been involved with Movimiento Cosecha GR during the first Trump Administration. What made you decide to be involved in the immigrant justice movement?

Jose – I am the son of two immigrant parents from Moyahua, Zacatecas, Mexico. I feel a deep sense of pride in being their son, as they moved here to better their lives. It would be dishonorable not to fight for immigrant rights because it could very well be my parents who need that support.

I moved to Grand Rapids in 2017, about a little more than a year into 45’s presidency. I felt that my skills in filmmaking could help people who look like me, talk like me, and have similar experiences to mine.

The biggest catalyst that made me want to take action against injustice was watching the footage of the Standing Rock conflict over the Dakota Access Pipeline. Seeing blatant white supremacy in action, treating Native Americans with such dismissal and disrespect, physically hurt me. One of my biggest regrets is not jumping on a plane to help in some way.

I believe that no one can be illegal on stolen land.

GRIID – You were involved Movimiento Cosecha GR when they began the End the Contract Campaign and when the Jilmar Ramos Gomez was sent to an ICE detention facility. For you, what about Jilmar’s case most impacted you, and why did you decide to make a film about what happened to him?

Jose – I really saw myself in Jilmar’s situation. I’ve been detained at the border multiple times before. I was filming a documentary series following famous Latino Athletes, and one of them was Mexican futbol star who played for the professional team in Tijuana. I would drive from Los Angeles to TJ by myself. For three weekends straight, border patrol sent me to secondary inspection each time. They’d search my car from head to toe, making me feel like a criminal. I thought to myself, “Do they not keep records of who crosses the border?”

Finally, I asked the agent inspecting my car, “Is this always going to happen when I cross the border?” He revealed that there was another Jose Guadalupe Jimenez, and apparently, he had quite the rap sheet. I asked if I looked like the guy, and he said no. Apparently, the other Jose is 4’11” and 150 pounds, while I’m 5’11” and 230 pounds.

A few months later, my wife and I were invited to a wedding in Buffalo, New York. We thought it would be a great opportunity to visit Toronto and see Niagara Falls. We flew to Toronto and rented a car to drive to Buffalo for the wedding. When we arrived at the US border, the agent saw my passport, and bing—a mini version of me popped up on his computer. He immediately ordered me to turn off the car, step out, and told my wife to stay put.

This was a rental car, so I was low-key scared someone might have left something in the trunk. Then, four border patrol agents with assault rifles arrived and escorted me into the building in front of a line of cars. I tried to joke around with the officers, but they were all business. They escorted me to a separate glass door and told me to wait until they could verify my identity.

Thirty minutes in, without any contact with my wife or the officers, I went up to the desk where an agent sat. I explained that this always happens when I cross the border and mentioned what the agent in Tijuana had told me about the other guy’s record. I asked if there was anything I could do to expedite the process. The agent replied, “You should change your name.” At the moment, I didn’t think much of it, but later, I felt angry. Why should I change my name? I love my name; it’s my dad’s name. I bet they let John Smith or Daryl Johnson in without any problems.

I’m not trying to equate what happened to me to what happened to Jilmar Ramos-Gomez, but it did sting. What happened to Jilmar was egregious, horrible, a shame, embarrassing, and insulting. If you google FUBAR, what they did to Jilmar should be a top search result.

It felt like this was exactly what Movimiento Cosecha said would happen. It was the evidence we kept presenting to the county commissioners.

I couldn’t stop thinking about how they treated him despite having his passport in his pocket, his Real ID, and being a veteran. It made me think, “How much more do you want from us?” It really drove home the point that it was never about being legal or “illegal” or having the right documents. It just proved to me that it was always a racial issue.

I felt like I had to tell his story or else no one else would.

GRIID – During a Cosecha community meeting, you said that it would be difficult to impact federal policy, but that people can influence and change things at the local level. Can you say a little bit more about what you mean?

Jose – What I was trying to convey is that sometimes we fall into 47’s mental game and fear tactics, which can make people feel powerless to make a difference. 47 will continue to be a racist today, tomorrow, and forever and I can’t change that. Changing policy on a national level is extremely difficult. However, after witnessing what Cosecha did here in Grand Rapids—showing up to county and city commission meetings month after month—and after what happened to Jilmar, proving what the community has been saying for months, it became easier, and dare I say, necessary for the sheriff to change the department’s policy detainers from ICE. I don’t think we would have seen that change so quickly without the pressure. I feel given the history of local law officials and politicians, I feel they would have tried to make it seem that Jilmar’s near deportation was an extraordinary occurrence. This then gave ICE no choice but to not renew its contract with Kent County. I realized that if every city did what Cosecha did, we could achieve real positive change.

I didn’t mean to ignore 47 completely, but I feel if we focus locally, we can effect change nationally.

GRIID – You are screening your film in January 15th at the Wealthy Theater here in Grand Rapids. After the film there will be a panel discussion about how to deal with the incoming Trump Administration’s threat of mass deportations. Do you see your film as a catalyst to move people to get involved in resisting deportations?

Jose – I hope so. At the very least, I feel the film will wake people up to the fact that the chess pieces for mass deportation are already set. I don’t think it will involve people being put on trains and rounded up like cattle or knocking on doors to see if people are speaking Spanish, as they did in the 1930s with the Mexican Repatriation Act and the 1950s with Operation Wetback. Not saying that isn’t a possibility, but I think the administration will try to really take advantage of local law enforcement to do their dirty work for them. There are plenty racial sheriffs and politicians are itching to deport not only Undocumented folks but anyone that might look or sound like us. We already know that they are going to increase participation in the 287(g) program, which deputizes sheriff’s departments to enforce immigration law. We are going to see detainers continue to racially profile Latinos like they did with Jilmar. It’s up to us to ask our local officials—in our case, the GRPD Chief, the new Mayor, the City Manager, and the city and county Commissioners, and our neighbors—”Are you going to treat us with dignity and respect, or are you going to be complicit and let them deport us?”

GRIID – Are you planning any future public screenings and how can organizations best contact you if they want to show your film in the future?

Jose – Nothing concrete yet. I think it’s really important that people see the film. I am open to screening it around Michigan, and hope organizations reach out to screen the film. I would send an email to at hola@josegjimenez.com if people are interested.

I also plan on submitting to film festivals to increase the reach of the film and make sure other cities across the country know Jilmar’s Story, know the community’s story.

Comments are closed.