Facilitating the Good Food Workshop: What happens when you challenge the West MI Nice culture

Yesterday, I was asked by the good folks at Access of West Michigan to facilitate part of a workshop that was meant to take a deeper look at the problems those who are involved responding to food insecurity have to come to terms with. In many ways, the facilitation was really about challenging the participant’s understanding of systems of oppression, but it was also about challenging what many in this area refer to as West Michigan Nice.

Yesterday, I was asked by the good folks at Access of West Michigan to facilitate part of a workshop that was meant to take a deeper look at the problems those who are involved responding to food insecurity have to come to terms with. In many ways, the facilitation was really about challenging the participant’s understanding of systems of oppression, but it was also about challenging what many in this area refer to as West Michigan Nice.

Two of the organizers with Access of West Michigan did a great job of looking at the history of food charity and how this response to food insecurity is completely inadequate. They also talked about the organization’s history and how Access of West Michigan has moved from a food charity to a food justice/food sovereignty model. The framing that these two presenters provided was a great way for me to transition to talking about Systems of Oppression and Structural Inequality.

I began with the slide above, to make the point that to achieve food justice, we must include all of the other aspects of movement building that are seen here as the roots or the foundation of the work to achieve food justice.

I also let people know that some of the content from my session was based on the recent book by Joshua Sbicca, Food Justice Now: Deepening the Roots of Social Struggle. One thing that Sbicca states early on is that, “ The current development of food justice should reflect the environmental justice movement’s insistence that environmental inequalities are not ultimately about the environment but about how structural inequalities harm people as they relate to the environment.”

In terms of food insecurity, the question is not that there isn’t enough food that is available to people, but there are systems of oppression that prevent people from eating healthy.

The Systems of Oppression that we touched (there are many more) were:

- White Supremacy

- Patriarchy

- Economic exploitation/Capitalism

- Heterosexism

- Ablism

- Anthropocentrism

I asked people to try to define each of these terms, but the other interesting thing about this list is that some people did not see Capitalism as a System of Oppression. Some said that it merely needed to be tweaked so that more people could have “opportunities.” This is a common response and completely understandable, since most people are not even aware of other economic models. What was also interesting is that since I said Capitalism was a system of oppression, people wanted me to give them an alternative. My response was, it didn’t really matter what I thought. Instead, I suggested that it is a questions best put to people, especially those most negatively impacted by Capitalism, to answer.

Next, I moved to a discussion of concrete manifestation of these Systems of Oppression, which I named as Structural Inequalities, listed here:

- Prison Industrial Complex

- Wealth Gap

- Institutionalized Racism

- Institutionalized Sexism

- Institutionalized homophobia and Transphobia

- State Violence against communities of color

- Corporate Power’s influence in the democracy

- Health Care system run by Insurance Companies and the

- Pharmaceutical Industry

- Energy Industry control over the energy we consume

There was less resistance to this list and I asked people to provide examples of what these Structural Inequalities looked like and how it affected people. There was no shortage of responses.

From there, we then talk about the importance of learning from social movements, particularly those that were led by communities of color. We briefly touched on the Poor People’s Campaign, the Farmworker Movement, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense and the Movement for Black Lives.

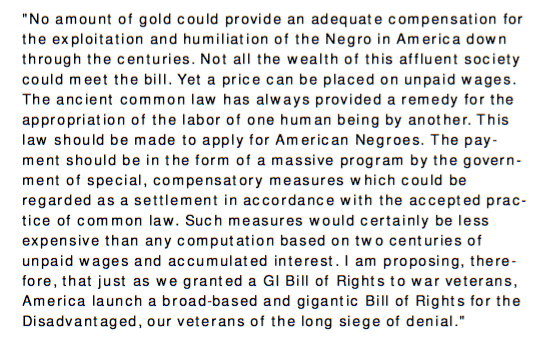

The Poor People’s Campaign, which grew out of the Civil Right Movement was demanding and end to poverty, decent housing and good jobs, particularly for the Black community. Dr. King used the idea that those in power could pay for the historic injustices that Black people have endure, what King called a promissory note, which is reflected in the vision Dr. King provides below.

The US Farmworker Movement, from the United Farm Workers to the Coalition of Immoklee Workers have fought and are fighting for the right to organize, better wages and working conditions, plus they have exposed a major injustice in the food system, the economic exploitation of the current agribusiness model.

Next we looked at the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. We talked about two things when it came to the Black Panthers. First, we discussed the radically imaginative vision expressed in their 10 Point Program, plus we talked about all of the amazing projects they created such as the Breakfast program and the drug rehabilitation programs.

![]() Lastly, we touched on the amazing work of the Movement for Black Lives. Here were look at just one aspect of their incredible platform, specifically the Invest-Divest portion of the platform.

Lastly, we touched on the amazing work of the Movement for Black Lives. Here were look at just one aspect of their incredible platform, specifically the Invest-Divest portion of the platform.

We then shifted gears to talk about some conceptual principles developed by Kirsten Valentine Cadieux and Rachel Slocum, listed here.

- Acknowledging and confronting historical, collective social trauma and persistent race, gender, and class inequalities.

- Designing exchange mechanisms that build communal reliance and control.

- Creating innovative ways to control, use, share, own, manage, and conceive of land, and ecologies in general, that place them outside the speculative market and the rationale of extraction.

- Pursuing labor relations that guarantee a minimum income and are neither alienating nor dependent on (unpaid) social reproduction by women.

Before getting to the group work of the workshop, I also talked about the importance of practicing Radical Imagination. Some aspects of Radical Imagination are:

Radical Imagination should take us from sympathy to solidarity.

- The Radical Imagination is “radical” not because of the answers it provides or the tactics it suggests, but because of the causes it seeks to understand.

- The Radical Imagination is not just about thinking different, it is about acting differently.

One additional way of framing Radical Imagination was this:

Radical imagination is re-envisioning your existence on this land without the inherited privileges of conquest and empire. It is accepting the fact of a meaningful prior Indigenous presence, and taking action to support struggles not only of social and economic justice, but political justice for Indigenous nations as well.

At this point we began to do group work that was not centered around food, but around issues that were confronting people, who are also food insecure. We had groups use radical imagination to come up with ways to dismantle the current Housing/Gentrification system, the for profit Health Care system, the unjust immigration system and the system of mass incarceration. However, before we broke into groups, we collectively discussed ways to dismantled poverty in Kent County.

I’m not going to share all of the ideas that people came up with, but I did want to say that there were a few take aways for me in doing this exercise. First, people really struggled to come up with ideas that operated outside of so-called free market system. This is understandable, considering how our expose to other models is limited. Secondly, when give the opportunity, people did exercise Radical Imagination that concluded that these systems could be abolished, because the participants could identify specific roots causes of mass incarceration and the other forms of structural inequality that we discussed.

The groups then did some reporting back, with brief discussion. I ended my portion of the workshop by making the point that, since everyone in the room was working to fight hunger and food insecurity, that our ultimate goal should be to put ourselves out of a job. What I meant by that is that if we really want to end hunger and food insecurity, then what we currently do – food pantries and other forms of food triage – would eventually not be needed. However, we all could end up doing something else, in terms of being part of community-based organizing, but that should really be determined by the people most impacted from Structural Inequalities and not those who have privilege.

The workshop ended with a panel consisting of people who are work in spaces that are addressing food insecurity. What I walked away with from the panelists were a few things. First, I heard that there needs to be more intentionality with regards to supporting and developing leadership that comes out of communities of color. The participants at this workshop were overwhelmingly White.

Second, instead of organizations “serving” the needs of the community, they need to ask those in affected communities what kind of support they need, but also what their larger vision of social transformation might be that would go way beyond whatever programs social service organizations can provide. Lastly, there were some practices that the organizations that the panelists were apart of that were moving in the right direction. For instance, at UCOM, one thing they have been doing is not requiring people to provide too much personal information, like social security numbers, since a majority of the people who access their resources are from the immigrant community. This shift in procedure was specifically to minimize the ability of ICE to gather more information on the immigrant community.

There wasn’t much time for a Q & A session with the panelists, but one question that did come up was, “What do we do next?” This is a common question that people, especially White people ask. The thing about this question is that it often means that people are looking for a quick fix to problems. The problem with asking the question, especially in this context is, that it means that people can easily avoid having to sit with the hard work of grappling with how Systems of Oppression and Structural Inequalities impact people. We all need to do more examination of how we participate in this kind of structural violence, own it and then maybe we can get to work on finding solutions.

The person who asked the question works at a church which provides meals to hundreds of people on a daily basis. This kind of triage work in important, in that it can have a positive impact on those who can access these meals. However, this is just a form of food insecurity triage, but it is not a solution. I responded by saying that, this is why we need to learn from the history of social movements. For example, the Black Panther Party for Self Defense used their breakfast program not only as a matter of feeding people in their community, but it also served to build trust. More importantly, it was one action that the Black Panthers took within a larger strategic plan that had a clear political vision within their 10 Point Program.

The Black Panther Party for Self Defense was not running a breakfast program as a form of charity, rather it was part of a larger community-based platform that was about greater community empowerment, political autonomy and the ability to fight the systems of oppression that are clearly laid out in their 10 Point Program. Unfortunately, most of the food charity programs in West Michigan are paternalistic and have no strategic purpose that could challenge the Systems of Oppression and Structural Inequalities that make up West Michigan Nice.

Comments are closed.