The Stonewall Uprising and the transformation of Pride Celebrations

This weekend people in West Michigan will celebrate the 43rd anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, the insurgent action that most acknowledge as giving birth to the contemporary LGBT movement.

The Stonewall Uprising was an unplanned act of resistance by gays and lesbians who frequented the New York bar known as the Stonewall Inn. The Stonewall Inn was owned by the son of a mob boss who tolerated gay and lesbian customers, although they were relegated to an area in the back of the bar.

The Stonewall Inn was not a well-kept establishment, but its subaltern nature provided space for the gay and lesbian community to at least have a place to interact and explore their own identities.

The NYPD was not tolerant of the gay and lesbian community, both from a legal point of view (dressing outside of one’s accepted gender norm could result in an arrest) and culturally, since the cops were and are a hyper-heterosexual and masculine institution, which would not tolerate gender bending in any shape or form.

The homophobic position that the NYPD took towards the gay and lesbian community was the norm, which resulted in constant harassment, abuse and arrests of the more flamboyant gays and lesbians, particularly Drag Queens. This abuse by the police was in some ways provoked as the gay and lesbian community began to more regularly defy the established norms and engage in public displays of affection, which of course the police found unacceptable.

As I mentioned earlier this was not a planned act of resistance nor was a polite or non-violent uprising. The authors of the zine Militant Flamboyance state:

Some of the arrestees began striking poses as they were being led off by the police while others arrested or confronted were mouthing off, and some threw their coins at the police. Still the cops continued to shove some arrestees into the police wagon. Some consider the most explosive moment to be when a butch lesbian was arrested and thrown in the wagon and began to rock it. Around this point in the night, some accounts speak of several spontaneous flashes of anger, a mass opposition, and militant refusal to accept the police harassment. One queen took off her high heel, smashed a police officer and knocked him down, grabbed his handcuff keys and freed herself. She then passed along the keys to her comrades, while others started to yell “Pigs!” “Faggot Cops!” and “Gay Power!” All of this led to the crowd transforming and growing into a mob, which began throwing everything possible at the police; bricks, coins, bottles, garbage cans, even dog shit.

The confrontation with the police lasted three days in late June of 1969 and involved hundreds of gays, lesbians and allies from the area who came out to participate in the uprising and defend their friends and lovers.

The Stonewall Uprising not only sent a message to the heterosexist power structure, it sent a message to other people who identified as gay, lesbian, bi-sexual or people who were just coming to terms with their sexual identity.

Following the Stonewall Uprising, those who had a history in the more closeted groups such as the Mattachine Society attempted to use the energy of the uprising that erupted in Greenwich Village and control it to serve its own strategic interest. However, those involved with the uprising would have nothing with their attempts to co-opt this insurgent movement.

Those who identified as gay, lesbian and bi-sexual decided to use the Stonewall Uprising as an opportunity to create a revolutionary organization and called it the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), in many ways modeled on many of the other radical groups that had come into being in the 1960s. The Gay Liberation Front was not focused solely on identity politics and made as part of their platform revolutionary principals that called for economic justice, an end to sexism, racism and US militarism abroad.

Months later a group that wanted to be more focused on gay and lesbian issues, the Gay Activist Alliance (GAA), formed and broke with the GLF. However, despite the Gay Activist Alliance not wanting to engage in inter-sectional politics, they did maintain a liberation-based worldview, which influenced their organizing strategy.

There was also the reality that those in the early LGB community who were not White and didn’t identify as a man felt that their concerns were either ignored or marginalized.

Radicalesbians was a lesbian caucus of GLF that split off and became its own organization and similarly, female activists left GAA to found Lesbian Feminist Liberation. There was also a group named Street Transvestite Action

Revolutionaries (STAR) that was founded to provide necessary services (like clothing, food and housing) to homeless trans and gender-variant young people living on the street, many of whom were involved in sex work. STAR also pushed existing gay groups to include transvestite and drag issues in their campaigns, as the gay organizations would often exclude them to appeal to politicians and straight citizens.

These tensions continued throughout the 1970s, but beginning in the 1980s the White, male sectors of the LGB movement became dominant and formed groups like the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), which took a much more assimilationist approach to organizing. Instead of calling for liberation and justice, HRC and other mainstream LGB groups called for the inclusion of gays, lesbians and bisexuals into existing social institutions such as corporations, the church and other hierarchical power structures.

From Commemoration to Beer Tents

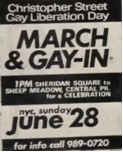

The very first Pride Celebration took place in 1970 in New York City called the Christopher Street Liberation Day. However, gay and lesbians groups did organize marches in Chicago, Los Angeles and San Francisco as well, where hundreds of people turned out. Many of these marches and parades were called Liberation or Freedom marches, which reflected the desires of those who organized these events.

However, by the 1980s, the anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising began to be run by more mainstream groups with the funding to do so. The Gay Alliance in New York reflects on this period:

In the 1980s there was a major cultural shift in the Stonewall commemorations. The previously, loosely organized, bottom-up marches and parades were taken over by more organized and less radical elements of the Gay community.

Now we have Pride events that are often held in more upscale parts of communities across the country, with more vendors than information tables and more entertainment than organizing campaigns.

Last year we interviewed Wick Thomas, an activist from Kansas City who confronted the elitist and exclusionary evolution of Pride in that community. There are also plenty of stories across the country where members of the LGBTQ community have challenged the failure of Pride events to make the spirit of Stonewall more central to the celebrations.

In Grand Rapids, like many other communities, the beer tent and photo booth are often more popular than information tables that are calling for a radical reorientation of the movement. Police Associations are welcomed, while LGBT youth and the Transgender community are targeted by cops.

In the early years of Pride in West Michigan, local campaigns were central to the celebration as is evidenced by the archival video we have about the 1988 Pride, where information tables dominated the physical space at Pride and the focus from the stage was on current campaigns and education.

I write these reflections on just before the 2012 West Michigan Pride Celebration, not because I know what is best for the LGBT community. I write these comments, like any historian, to get us all to think about where we came from and hope that it informs where we go from here.

Trackbacks