This Day in Resistance History: Remembering the Dublin Lock-Out

On August 26, 1913, the Dublin Lock-Out began. This was one of the longest and most difficult strikes in modern history, and its story is one of struggle, solidarity, betrayal, and bloodshed.

The Dublin Horse Show, held in August by the Royal Dublin Society, was one of the elite’s favorite yearly events. The workers of Dublin’s extensive tram service went on strike just as the show was starting, in order to get the attention of wealthy capitalists and cause the greatest disruption to the elite class.

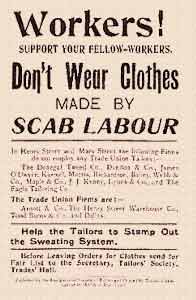

The union workers were protesting horrific working conditions set by William Martin Murphy. He was the owner of the tram corporation as well as Dublin’s largest department store, Ireland’s major newspapers, and the Imperial Hotel. He was also the major stockholder in Ireland’s railway system. His tram employees worked on schedules of 11 to 17 hours a day. Murphy paid workers to be informers on their peers and harsh discipline was handed out to anyone who violated even the most minor rule. The week before the lock-out, Murphy had met with 300 tram employees and got them to agree not to join or aid any union members. He then fired 340 workers he suspected of belonging to the newly founded union.

On August 26, trams were stopped along their lines and abandoned by their drivers. Murphy snapped into action. He rallied 400 of Dublin’s employers to threaten their own workers against unionizing and to force them to sign anti-union and anti-strike pledges. To make sure that their shops remained non-union, Murphy struck a deal with the business owners. They each deposited a large sum into an account called “The Employers’ Federation.” Murphy then went to the bank and arranged that if a shop was unionized, the employer would lose his deposit.

Murphy also controlled the media, and the message, about the strike. He published a series of articles stating the resistance was about to collapse. He depicted the unionized workers as debauched and slovenly, claiming that even if their wages were raised, they would just drink it all away. Employers who were keeping wages low were therefore protecting public safety and helping to keep the “lower classes” sober.

These preliminary tactics failed, and thousands of workers joined the tram workers in their strike. They were locked out of their jobs as a result. Within a month, 27,000 workers in Dublin were on strike. By mid-October, 32 unions representing more than 30,000 workers had shut down nearly all of Dublin’s businesses.

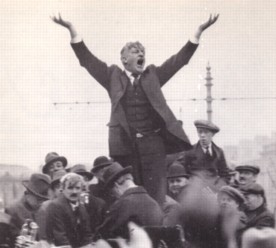

On August 31, Jim Larkin, leader of the tram workers’ union, was let out of jail on bail. A rally was planned, and hundreds of police officers stood nearby, looking to re-arrest Murphy. They were unprepared when he turned up to speak—from the balcony of Murphy’s own Imperial Hotel, having slipped past guards in disguise. He was arrested before he start his speech, and the police attacked the crowd. Hundreds ended up in city hospitals with injuries. Two workers were killed in the streets, and a third was tortured to death in a jail cell. A fourth worker was shot as she returned home from the rally.

But perhaps the cruelest intervention by William Murphy against the strikers came that fall, and it involved the most powerful of his allies: the Roman Catholic Church. Union workers in Ireland had corresponded with British trade union groups, who agreed to shelter the Irish workers’ children until the end of the strike. Without wages, many families were starving, and the union had run out of money for its food kitchens.

Dublin’s Archbishop Walsh wrote a letter that Murphy published in all of his newspapers. The letter claimed that that the entire plan was a scheme to turn the children into Protestants. It said, in part, “… they can no longer be worthy of the name of Catholic mothers if they so far forget that duty as to send away their little children to be cared for in a strange land, without security of any kind that those to whom the children are to be handed over are Catholics or…persons of any faith at all.”

Walsh also argued that once the children had lived in comfortable homes with three meals a day, they would be unfit to return to their lives in Dublin and its much lower standard of living (due, of course, to the “debauched natures” of the Irish working class).

Some mothers were convinced by the letter or by their own priests not to send their children away. Others faced harsher manipulation. As children were taken to the waiting boats, Irish priests organized groups of weapon-carrying men to block them from boarding. Some children did manage to escape to England, but many were left in Dublin where their parents had no money to care for them. Murphy’s newspapers portrayed Jim Larkin as the villain in this action, a man who had to be stopped as he attempted to steal Ireland’s youth and future.

British trade unions responded by sending ships of food supplies to the Dublin workers. This made it possible for the strike to continue, and for families to at least provide a subsistence level of food for their children. By January, two meetings had been held with the Employers’ Federation without any positive outcome. Many workers could hold out no longer and began accepting individual offers to return to their jobs.

A core group of 5,000 union members tried to keep the strike alive, even after it had been officially broken. They launched court challenges, and in October 1915 they won a case against the Dublin Steam Packet Company. But most workers were forced at some point to return to non-union shops to find jobs.

William Butler Yeats wrote a scathing poem, “September 1913,” which attacks the Employers Federation, the colluding banks and press, and the Catholic Church in the parts they played in thwarting the unions of Dublin. He pictures the capitalists as they “fumble with their greasy till” adding “halfpence to the pence,” while depriving the working class of a decent living. Of the strikers and other Irish revolutionaries, he wrote:

Yet they were of a different kind,

The names that stilled your childish play,

They have gone about the world like wind,

But little time had they to pray

For whom the hangman’s rope was spun And what, God help us, could they save?

Yeats’ poem reflects the demoralized feeling of many after the collapse of the strike. The rebuilding of the broken union system was slow, and it was not until 1919 membership in unions in Dublin finally reached levels matching those of 1913, when the lock-out began.

But for seven months, Dublin’s working class had put everything on the line in an attempt to face down the wealthy who controlled their lives and their right to reasonable working conditions. And Irish employers, many of whom had lost money and even gone bankrupt during the lengthy strike, never again tried to break a union the way that William Martin Murphy had in 1913. Today, 37 percent of Ireland’s full-time workers belong to a union.

Trackbacks