This Day in Resistance History: A Second Look at Guy Fawkes

On this day in 1570, Guy Fawkes, the most hated man in England, was born in the city of York. A Roman Catholic convert, Fawkes was born during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, who became gradually more intolerant of Catholics when it became clear that her cousin, Mary Queen of Scots, had designs on the English throne. Elizabeth died childless, and it was Mary’s son, James VI of Scotland, who succeeded her as King James I of England. At the time, Guy Fawkes was a soldier of 33, fighting for Spain.

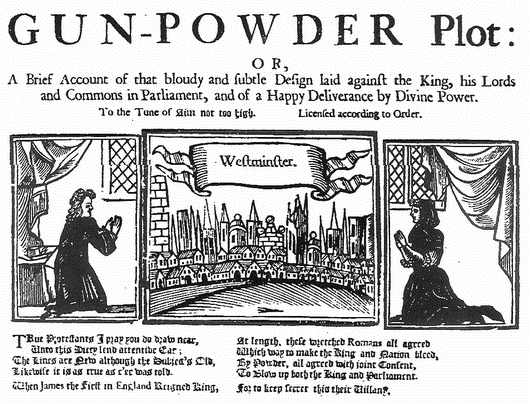

Fawkes is famous for his role in the Gunpowder Plot, a failed attempt to assassinate King James I and replace him with his Catholic daughter. Reviled in mainstream history texts as a scheming partisan criminal, Fawkes has also been dismissed by many anarchists as being a monarchist—someone who believed that by replacing one ruler with another, he would somehow improve conditions for the common people of England.

But Fawkes and his fellow plotters may well have had a larger vision than just doing away with James I: they may have planned not only for a country of promised religious tolerance, but also of fewer aristocrats and a more democratic style of Parliamentary government.

When James I first took the English throne, he promised the people that there would be no more religious persecution as long as the Catholics remained peaceful and followed the kingdom’s laws. But after he was safely in possession of England and not facing an uprising, he reportedly said, “No, good faith, we do not need the Papists now.”

In some mainstream history lessons in the UK, you will still find the idea that James I practiced religious tolerance right up until the Gunpowder Plot, but that is not the case. A conservative Protestant who was obsessed with witchcraft and satanic possession, not only did James I resume the execution of Catholics for heresy, he also enforced harsh recusancy fines—fines for not attending Protestant services. The fines were affordable for the upper class, but the working class had to pay a shilling a week, onerous for many. He also ordered that all of the Catholic priests in England leave the country. The irony of this is that James’ queen, Anne of Denmark, was a secret Catholic, and was allowed to hold mass at his palace at Whitehall.

But this double standard was far from James’s only shortcoming as a monarch. He believed, much more strongly than his cousin Elizabeth, in the divine right of kings. This was hardly a new idea, but James bumped it up a few notches in his writings. He explained that kings were actually higher beings, more akin to angels than humans. “Kings are justly called gods,” he wrote, and “the state of monarchy is the supremist thing upon earth.” Therefore, they were the perfect stewards of God’s plan on earth. James did not believe in parliamentary government, and told his son, “Hold no parliaments but for the necessity of new laws, which would be but seldom.” It was obvious to James that kings were the true authors of law, since they were divinities in their own right.

So when Guy Fawkes and his fellow conspirators planned to blow up the House of Lords during a meeting of Parliament with King James I, they were fully aware that although one outcome of success would be placing a more sympathetic monarch on the throne—another was it would weaken the power of the House of Lords. It would take another generation to replace all the dead peers, who had to be succeeded by their heirs. Meanwhile, there would be opportunities for stronger rule by the House of Commons and representatives more closely associated with the working people of England.

Admittedly, the plan was short-sighted because of its limited outlook. Although the Gunpowder Plot participants were searching for a way to a better world, they failed to see how the religious divisiveness that they hated was actually a way for those in power to keep the working class from uniting against those in power.

On the night of November 4, Guy Fawkes was discovered in a cellar beneath the House of Lords’ chamber of Parliament, guarding a large pile of firewood. When he was searched, he was found to be carrying a pocket watch and several “slow matches” or fuses. The firewood was concealing 36 barrels of gunpowder. He was arrested at dawn of November 5 and taken to the Tower of London. Even under torture, Fawkes insisted that he was acting alone, and refused to give up the names of his fellow conspirators. Finally, using information they had obtained from other sources, the torturers created a confession document, dated November 17, which a broken Fawkes finally signed.

On the night of November 5, announcing that he had been delivered from murder, King James I ordered that bonfires be lighted across Europe in celebration. Many towns and villages burned Guy Fawkes in effigy, a custom that continues to this day.

There are indications that King James and his advisors knew about the Gunpowder Plot well in advance of November 5, and allowed it to play out with the intention of using it to whip up more hatred of Catholics in the country. And if that was the intended outcome, it worked very well. Suspicion of Catholics reached an all-time high in the kingdom after November 5, 1605. After the attack, King James I, in addition to setting the “popish recusants” fines even higher, was able to institute an Oath of Allegiance. This required Catholics to swear that the Pope had committed heresy by ruling that Protestant princes (such as James) should be excommunicated.

The King also put “shock doctrine” techniques into play: he used the confusion immediately after the Plot to seize two-thirds of the lands held in his kingdom by Catholics and added them to the crown’s possessions.

A Gunpowder Plot test conducted in 2005, using the same amount of gunpowder in an enclosed space the size of the Parliamentary cellar, found that everyone in the House of Lords and within 300 feet of the chamber would have been killed—even if only half the gunpowder had ignited on that night of Guy Fawkes’ arrest.

Maybe that’s why every year at the opening of Parliament, the Yeomen of the Guard go into the cellar to officially search for kegs of gunpowder. Or perhaps this ceremony is a reminder that no one dare question the power and authority of those controlling the United Kingdom. This year, the members of both Houses should probably be looking in the streets instead of the cellars. Having set aside the manufactured divisions of religious affiliation, workers in Great Britain are planning a general strike to take place this year.