Co-Founder of SNCC, filmmaker Judy Richardson speaks to GVSU audience on MLK Day

About 300 people walked silently in the cold today at the GVSU Allendale campus to kickoff a week of events commemorating the birth of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

As people wove through the campus they walked past signs that provided a chronology to the life of Dr. King. Some signs also included statements from Dr. King while others highlighted actions that he participated in during his short lived 39 years.

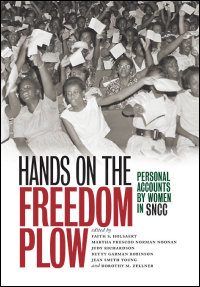

The silent walked ended and people filed in doors to hear the words of one of the founding members of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Judy Richardson. Judy was a graduate of Moorhead College is a co-producer of the Eyes on the Prize series and author of the recently released book Hands on the Freedom Plough: Personal Accounts of Women in SNCC. The civil rights activist is also the director of the documentary Scarred Justice: The Orangeburg Massacre 1968.

After making a few opening comments, Richardson then shows a clip from the film, a clip which provides a context for the community of Orangeburg where the students massacre took place in 1968.

According to Richardson, the majority of the population in the area was Black, but White people controlled all the power, both politically and economically. This White Supremacist power structure was threatened when students began to confront the owner of a segregated bowling alley.

Students began asking questions about how a local businessman could exclude people from his business. After four days of protests the campus was under lockdown, with local and state police, along with National Guardsman. Police open fire without warning killing 3 college students, one high school student and wounding 28 others. Journalists that Richardson interviewed for the documentary said that all the students were shot in the back.

During the interview process they came across two White journalists who wrote a book about the massacre. One went into the hospital to interview those wounded and told the hospital personal that he was with the Bureau. The hospital thought he was with the FBI, when in fact he was the Bureau chief for the LA Times in Atlanta. Gaining access to the medical reports proved that students were shot from behind, suggesting they were all running away when police & National Guardsmen opened fire on the demonstrators.

Richardson said that the film premiered at the annual event to commemorate the massacre at South Carolina State College. She also spoke about the film production process and particularly the interview they did with Bill Barley. Barley was with the Governor’s office at the time of the shooting and was willing to talk about what had happened. When the film crew arrived at his house Barley was somewhat embarrassed since he didn’t know Judy was a Black woman. Matters were complicated when Barley told them he collects Confederate Flags. However, Richardson said that he was very forthright with what he had to say, which was to tell the truth about what happened that day in 1968.

Richardson also talked about how this event was history that had been hidden and until recently rarely talked about as part of the freedom struggle of the 1960s. She said that the Orangeburg massacre was never part of the larger public consciousness in the same way that the 1970 Kent State shootings were. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young did not produce a song about Black students being shot in the back.

The filmmaker also talked about how the current Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour, when asked about race relations at that time said he didn’t remember it being “that bad in the 1960s.” Barbour also stated that the White Citizen’s Council were a “positive force in the community.” Richardson pointed out that the White Citizens Council were the ones bankrolling the activities of the local KKK chapters.

For instance, in Yazoo City, Mississippi, where Medgar Evers was doing organizing work, Blacks who had signed a petition had their names published in a newspaper ad, along with death threats and job loss. “This is why,” Richardson said, “it is so important to remember history and to recover it. If we don’t we end up with people learning about the civil rights struggle through films like Mississippi Burning.” Mississippi Burning was a 1988 film that depicted FBI agents as the real heroes and risk takes of the freedom struggle in Mississippi.

After her comments Richardson listened to comments and questions from the audience. Several people asked the speaker “what they could do” or “what lessons should we learn from this history about the struggle for civil rights?” This is always a difficult question for anyone to answer, since it assumes they can tell people what to do. However, Richardson did a great job of getting people to think about the importance of becoming educated about this part of history. She also felt that it was important for people to act, to organize, to start something for change or seek out groups that are already doing that work. Richardson really stressed the importance of popular education or study groups and cited A People’s History of the United States as a great text for reclaiming that history.

There were also several GVSU students who talked about being punished for skipping class to come to this hear Richardson, since the university does not give students the day off or have a policy of allowing students to attend events, even if it means missing classes. Someone from the university responded and invited students to be part of a committee to address this matter, but this writer had visions of students having a sit-in or occupying the administrative building to demand that the school have a clear and committed policy on celebrating MLK Day. Such an action would be a “lesson learned” from the kind of history that Judy Richardson shared with people on this day.