Statue of Catholic Bishop sanitizes historical genocide against area Native People

Yesterday, the Diocese of Grand Rapids unveiled a statue of Bishop Frederic Baraga, a nineteenth century catholic clergyman that some are now pushing for sainthood.

Baraga, according to some sources, founded a mission in what would become Grand Rapids, but his real legacy is the work he did in the northern part of Michigan and the UP.

Much of the news coverage of the statue ceremony states that Baraga did a great deal of missionary work amongst the Ojibway. The statue of Baraga has several bronze tablets around its perimeter, with one of them stating that Baraga created an Ojibway-English dictionary, “that is still in use today.”

While Baraga comes across in the media and church accounts as a saintly man, there is something that is glaringly missing from what function the bishop played in the colonization of the Great Lakes region.

What has come to be the acceptable norm in the US is that those who do missionary work are highly respectable individuals. However, the fundamental nature of missionary work is to not only convert people to your beliefs, but to automatically denounce the existing spiritual traditions of those you mean to convert.

More importantly, Baraga’s interaction with the Ojibway people also paved the way for genocidal policies that Europeans have implemented over the past 150 years in this area.

Those policies include the outright killing of Native people, stealing Native lands, forced relocation and taking Native children from their communities to put them in boarding schools, something the Catholic Church did in Michigan. The history of these boarding schools included denying Native children to speak their language, dress in traditional clothing, subjected to Christian teaching and also physical and sexual abuse, as is well documented in Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools.

This is the legacy of Bishop Baraga, however well intentioned he was, since his committed to converting the Ojibway paved the way for the harsh policies that followed.

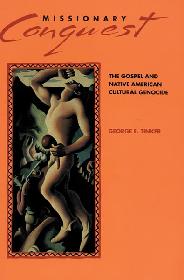

Native American scholar George Tinker, author of the book Missionary Conquest: The Gospels and Native American Genocide, refers to Christian missionaries to Native Nations as “partners in genocide.”

Tinker goes on to describe the significance of White missionaries this way:

Told from an Indian perspective, the story is far less entertaining and much less endearing. Pain and devastation become dominant elements as Indian anger erupts to the surface. Indeed, today the white missionary, both in the historical memory of Indian people and in the contemporary experience, has become a frequent target of scorn in most segments of the Indian world. Many implicitly recognize some connection between Indian suffering and the missionary presence, even as they struggle to make sense not only of past wrongs, but also of the pain of contemporary Indian experience. The pain experienced by Indians today is readily apparent in too many statistics that put Indians on the top or bottom of lists. For instance, Indian people suffer the lowest per capita income of any ethnic group in the US, the highest teenage suicide rate, a 60% unemployment rate, and a scandalously low longevity that remains below sixty years for both men and women.

Not surprising, such commentary did not accompany the unveiling of the Baraga statue yesterday. The lack of this kind of critical voice or perspective reflects how deeply ingrained the dominant culture, a culture of conquest, is in this country and this community.

The celebration of the unveiling of the statue of Bishop Baraga not only legitimizes what was been done to Native communities, it normalizes and sanitizes the history of genocide in the Americas.

thank you for sharing this